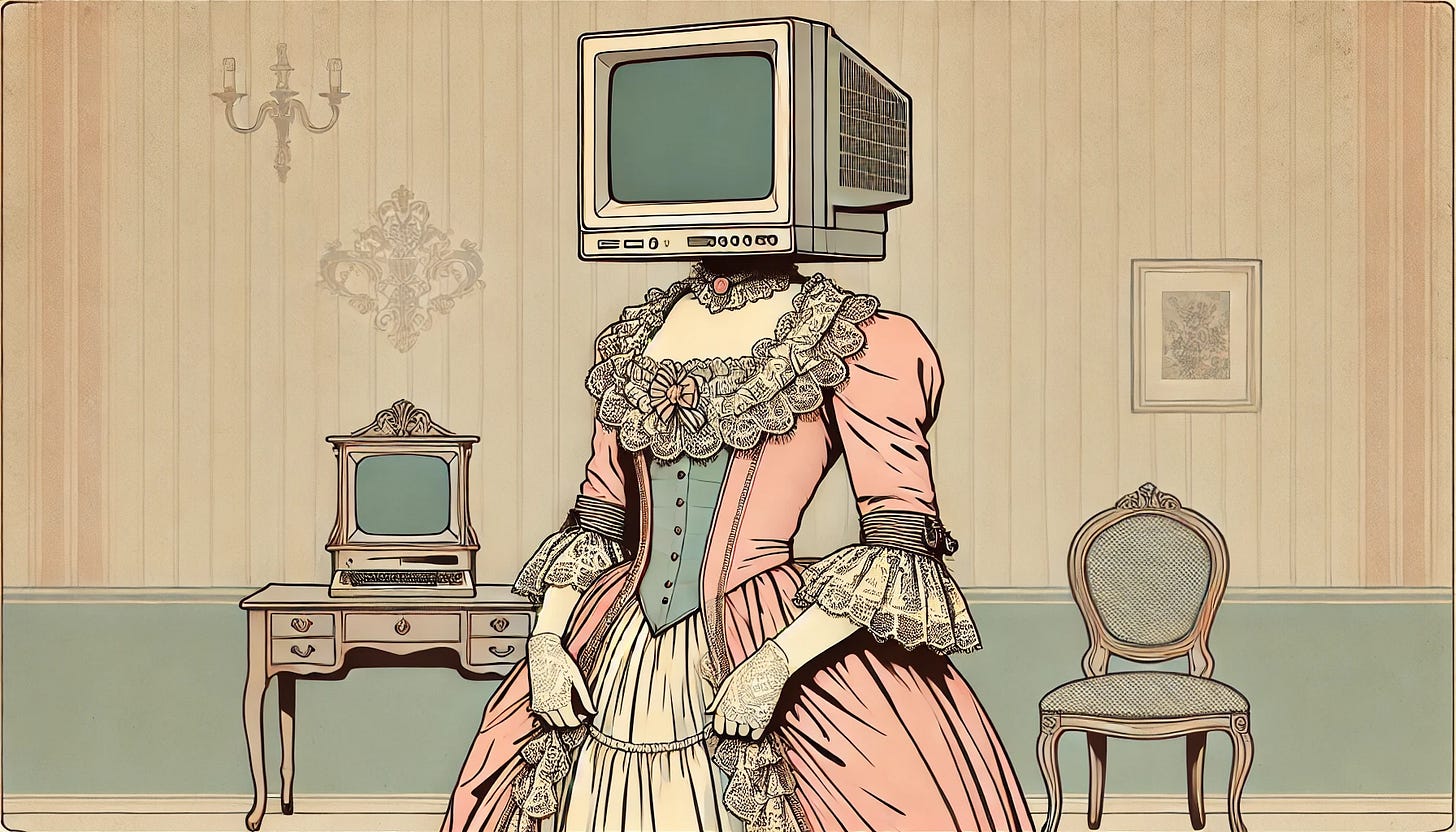

Girl With A Computer Head

On feminine roots, forgotten networks, and what tech was before it became power

She wasn’t in the system. She was the system.

Every Unscripting Life episode begins with the same image: a girl with a computer instead of a head. At first, it seemed like a simple metaphor for our digital age—a fusion of human and machine, a comment on how deeply technology has become embedded in our sense of self. A nod, perhaps, to Steve Jobs’ idea that the computer is a bicycle for the mind.

But lately, I’ve started to feel there’s something more layered beneath it. Something softer. Something more female.

I’ve just begun reading Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet by Claire L. Evans—who, I have to say, looks dangerously cool—and even a few chapters in, it’s already reshaping how I see things. The book brings forward the overlooked presence of women whose intellectual labor, emotional stamina, and collaborative instincts quietly shaped the foundations of what we now call “tech.” It’s clear how much care and research went into this book—I admire Claire deeply for doing the work to bring these stories back into the light.

It doesn’t follow the usual arc of invention and disruption. The tone is gentle, the writing full of quiet reverence, tracing stories that were nearly lost. It feels like an act of restoration—and it fits under the umbrella of Unscripting Life in the most natural way.

These are unscripted stories—contributions never written into the script of power, yet deeply woven into the fabric of our digital world.

Before computers were machines, computer was a job title. A human one. The task: to perform calculations—sometimes astronomical, sometimes military, sometimes mundane. And this role was overwhelmingly filled by women. They were precise, detail-oriented, and often overlooked.

Ada Lovelace is one of the earliest names in this lineage. Born in 1815, she was the daughter of the poet Lord Byron and Annabella Milbanke, a highly educated woman known as the “Princess of Parallelograms” for her passion for mathematics. After a brief and troubled marriage to Byron, Annabella became determined to shape her daughter’s mind through discipline and reason. She believed that a life structured around logic could shield Ada from the emotional instability she had seen in Byron. Mathematics became a form of protection—a path to stability.

From an early age, Ada showed signs of a restless, visionary intellect. She immersed herself in abstract mathematics, imagined elaborate flying machines, and developed a fascination with the idea that symbols and patterns could extend far beyond numbers. As her interest in mechanical computation deepened, it unsettled her mother. The intensity of Ada’s imagination didn’t fit into the carefully planned mold. It carried echoes of the very poetic temperament Annabella had tried to suppress.

In her twenties, Ada began working with Charles Babbage, who was developing a theoretical calculating machine called the Analytical Engine. Ada translated and expanded on a technical paper about the machine, adding extensive notes that explored how it could be used to perform operations beyond arithmetic—language, symbolic manipulation, even musical composition. These notes, published in 1843, are now considered the first computer program. Her work imagined a future in which machines could process not just quantities, but ideas—a century before that future became reality.

Her work was not an anomaly. It was a beginning.

As computing grew, it became industrialised. In observatories and labs across the world, women were hired en masse to perform calculations—mapping the stars, charting the movements of celestial bodies, building the scaffolding for modern astronomy. They were often paid less than factory wages for work that required deep focus and mathematical precision. In many ways, they were treated as interchangeable parts in a scientific assembly line—valued for their steadiness, but rarely credited for their insight.

In the early days of telephony, women also formed the connective tissue of our communication networks. Switchboard operators—8,000 of them in 1891, a quarter million by 1946—became the human routers of the world. They weren’t just plugging wires. They were translating human need into action, building a living map of connection.

What stays with me is the way women formed the core of it all—the infrastructure, the living logic, the original interface. Their lives weren’t always confined to the home or the kitchen. They shaped the systems not from the sidelines, but from within, stitching together the early architecture of connection and computation.

Today, tech is largely dominated by men. That shift is worth pausing over. Maybe the book will offer more insight into how that happened. Still, I keep wondering: Did computing begin to draw in a different energy once it evolved from a support function into a system of power? Once it moved from background to frontier? Like steam, electricity, or the automobile before it, computing became a new kind of revolution. And revolutions, especially those that promise control and scale, often attract those drawn to hierarchy, legacy, conquest.

Biologically, socially, historically—men are more likely to chase dominance. To spread their influence, scale their reach, and secure status. Women, by contrast, are often socialised—and perhaps even wired—to prioritise connection, to build and maintain networks, to foster relational ecosystems. Not always. But often enough that we see the residue of these patterns in how our systems evolve.

In a strange and deeply ironic twist, the very system that was enabled by feminine labor, intuition, and social intelligence became a realm that increasingly excluded them. The logic of care gave way to the logic of power. The connective became competitive.

That’s the paradox I keep circling.

This girl with the computer head holds something older than it seems. She gestures toward a past where women built the invisible systems that still shape us—calculated trajectories, routed voices, imagined machines before they existed. She carries the presence of those who shaped the foundations of computing from the inside out. Women who built, mapped, translated, and made sense of complexity long before tech had a name for it. Their work wasn’t an entry into tech. It was tech. A deep, quiet lineage running through its core.

I’ll be weaving more from this book into the next few episodes of this publication. There’s something about this history—its gentleness, its grounding—that feels like an essential part of the larger story we’re trying to tell.

Maybe Unscripting Life is my way of tracing that thread back through the noise. Of remembering that the digital world didn’t always speak the language of dominance. It once spoke the language of care, complexity, and connection.

And maybe, if we listen closely, it still can.

Much like Generative AI—an eerily intuitive, collaborative, language-based technology—feels inherently human. And perhaps even, in some quiet way, inherently female. Its strength lies not in conquest, but in communion. Not in control, but in conversation.

Maybe that’s not a coincidence.

Maybe that’s a return.

ADRIANA